Small Assembly Interpreter

A sample Assembly program that calculates GCD this interpreter can run

A sample Assembly program that calculates GCD this interpreter can runIntroduction

This Assembly Interpreter is able to parse and execute programs written in the assembly language, modeling the behavior of the programs as if they were executing on a simple computer processor.

It models a stack-based computer architecture whose processor has at least eight registers: one program counter (called PC), a stack pointer (called SP), and six general-purpose data registers (called R0, R1, R2, R3, R4, and R5). The program counter stores the address of the currently-executing instruction. Each data register stores a 32-bit signed int (identical to Java’s int type) that can be modified or moved to or from memory. Each memory location stores an instruction or a signed 32-bit int. The stack pointer, instruction set, and related conventions provide architecture-level support to treat part of memory as a stack, simplifying in-memory storage of local data and the implementation of subroutines.

Supported Instructions

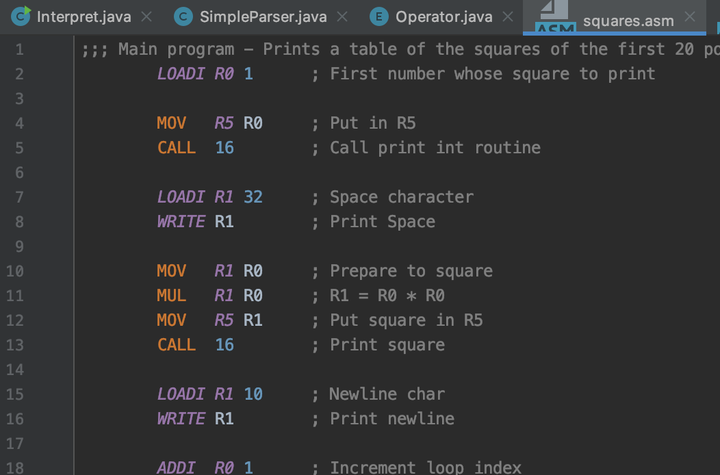

The interpreter currently supports the following assembly instructions:

Data movement instructions. The following instructions move data from one location to another, and then advance the program counter to the next instruction:

- MOV dstReg srcReg: “Move.” Copies the value of register srcReg to register dstReg.

- LOAD dstReg srcAddrReg: Copies a value from memory to register dstReg. Register srcAddrReg contains the memory address of the value to be copied.

- LOADI dstReg val: “Load immediate.” Sets the register dstReg value to val.

- STORE dstAddrReg srcReg: Copies the current value from register srcReg to the memory address currently stored in register dstAddrReg.

Arithmetic instructions. The following instructions perform some arithmetic operation, and then advance the program counter to the next instruction:

- ADD sumReg valReg: Adds the value stored in register valReg to whatever value is currently stored in register sumReg, replacing whatever was previously stored in sumReg, i.e., sumReg += valReg.

- ADDI sumReg val: “Add immediate.” Adds the constant val to whatever value is currently stored in register sumReg, replacing whatever was previously stored in sumReg.

- SUB differenceReg valReg: Subtracts the value in register valReg from whatever value is currently stored in register differenceReg, i.e., differenceReg -= valReg.

- SUBI differenceReg val: “Subtract immediate.” Subtracts the constant val from whatever value is currently stored in register differenceReg.

- MUL productReg valReg: Multiples whatever value is currently stored in register productReg by the value stored in register valReg.

- MULI productReg val: “Multiply immediate.” Multiples whatever value is currently stored in register productReg by the constant value val.

- DIV quotientReg valReg: Divides whatever value is currently stored in register quo- tientReg by the value stored in register valReg, storing the result (the quotient) in quotientReg.

- DIVI quotientReg val: “Divide immediate.” Divides whatever value is currently stored in register quotientReg by the constant value val, storing the result (the quotient) in quotientReg.

- MOD remainderReg valReg: Divides whatever value is currently stored in register remainderReg by the value stored in register valReg, storing the remainder in remain- derReg.

- MODI remainderReg val: “Mod immediate.” Divides whatever value is currently stored in register remainderReg by the constant value val, storing the remainder in remainderReg.

I/O instructions. These instructions read or write input and advance the program counter to the next instruction:

- READ reg: Reads a single character of input from the user, setting the value of register reg.

- WRITE reg: Writes a single character to the screen, from the low-order 16 bits of register reg.

Control-flow instructions. The following operations change (or conditionally change) the next instruction to execute, (possibly) resetting the program counter to a specific value rather than just advancing it to the next instruction:

- JUMP addr: Sets the program counter to the value addr. • JUMPZ reg addr: “Jump if zero.” If the current value in register reg is zero, sets the program counter to addr.

- JUMPP reg addr: “Jump if positive.” If the current value in register reg is positive, sets the program counter to addr.

- JUMPN reg addr: “Jump if negative.” If the current value in register reg is negative, sets the program counter to addr.

- HALT Stops executing the program.

Stack instructions. These instructions allow the programmer to treat some portion of memory as a stack, and simplify the implementation of subroutines. The stack is implemented as a moving pointer (stored in register SP) that starts at the end of memory. The pointer value decreases as values are pushed (copied into memory) onto the stack, and the pointer value increases as values are popped (copied from memory) out of the stack. Intuitively, the stack pointer points at the next memory location to be written if a value is pushed onto the stack.

In addition to being accessed and modified by the instructions below, the stack pointer may be accessed as if it was a general purpose data register; it is common to compute memory addresses relative to the stack pointer, to access data (such as subroutine arguments) that has recently been pushed to the stack.

- PUSH reg: Pushes a register’s value onto the memory stack. In other words, stores the value from register reg into memory at the address currently stored in register SP (the stack pointer), decrements the stack pointer, and advances the program counter to the next instruction.

- POP reg: Pops a value from the stack into register reg. In other words, increments the stack pointer, loads the value from the memory address at the (newly-incremented) stack pointer into register reg, and advances the program counter to the next instruc- tion.

- CALL addr: Calls a subroutine at the given address. In other words, pushes the return address (the next-higher instruction from the current program counter) onto the stack, and sets the program counter to addr. By convention, the argument (if any) to the subroutine should be placed in register R5 and any subsequent arguments should be pushed to the stack before the CALL instruction. Also by convention, the subroutine (the callee) is responsible for saving and restoring any registers, except R5, that would be overwritten by the subroutine.

- RET: “Return.” Returns from the current subroutine. In other words, pops the address off the stack into the program counter. By convention, the subroutine should store its return value in register R5 and restore the values of any registers that were saved at the beginning of the subroutine, before the RET instruction.

Extensibility of Design

This assembly interpreter has three main components: Machine, Parser, and Instruction. Each of the component is designed for extensibility which allows easy migration to a different machine architecture and/or integration of new assembly instructions.

Machine

The Machine class extends the AbstractMachine abstract class which defines APIs and implements

some functionalities on data storage (registers and memory (including stacks) operations) and some

runtime methods (e.g. run(), halt(), readChar()).

The rest of the

interpreter’s implementation does not depend on the underlying implementation of Machine (e.g.

how registers and memories are simulated) but rather they call the APIs provided by the abstract

class AbstractMachine. Therefore, it is easy in the future to implement another machine architecture,

say, QuantumMachine. The programmer could simply create the class and extend AbstractMachine while

keeping the rest of the interpreter still functioning on their current implementation.

There is indeed one assumption made for AbstractMachine: the registers can be indexed, in

some way, using integers. However, this does not seem to be a much bothering thing for most

architectures.

Parser

The current SimpleParser class implements the interface Parser. Again, the rest of the interpreter’s

implementation does not depend on this specific SimpleParser implementation. In the future, if

a more complex parser is required (e.g. one that supports labels), the programmer can simply create

a AdvancedParser class that implements the Parser interface, and the interpreter would still work

fine.

Instruction

The Instruction class is a wrapper of the two components of an assembly instruction: the Operator enum

and its arguments. To add a new instruction, simply add another item in the Operator enum and override

the abstract method execute(AbstractMachine machine, int[] args). The usage of Java enum here, in many ways

as described in Effective Java, makes the integration of new instructions safer and easier (compared to switching

on C-style constants or creating new inherent classes). Additionally, this solution records the number

of required args for an Operator to execute in the enum. The SimpleParser implementation checks the correctness

of the given .asm source file to see if the number of given arguments match the requirement and this

is checked again during runtime by the execute method in case of a memory corruption.